Understanding the future is the ultimate competitive advantage. Defining strategies and making decisions become a whole lot easier if you already know where the future is taking us. Unfortunately, knowing the future is incredibly difficult…but that doesn’t seem to stop us trying.

- People buy lotto tickets hoping they’ve predicted the winning numbers.

- Property investors buy property expecting to make a capital gain.

- Executives create annual budgets that determine spending priorities for the next 12 months.

Now perhaps this feels like an unfair comparison, and in some ways you’d be right (but perhaps not for the reasons that you’d expect). But if I was being unfair to anyone in this comparison it would be property investors. Well, perhaps not all property investors, but at least long-term property investors. Long-term property investors aren’t too concerned about whether they are right in the short-term. They believe, and the evidence is there to support them, that over the long-term property values go up. So although there is a bonus in buying property at the bottom of a property cycle, over the long-term it won’t make that much of a difference.

Buying lotto tickets and creating budgets (along with any other form of strategic decision making) is, like property investment, a bet on the future. But unlike property investing, the odds of getting it right over the short-term, or even the long-term are not stacked in your favour. The odds of winning lotto are something like 8,000,000:1 which means that if you were to play the same set of numbers for both the Wednesday and Saturday draw for approximately 78,000 years you should expect to win the jackpot once.

And yet I would tell you these are better odds than you creating an accurate 12 month budget.

“Heresy!” you say? Yet, this is the truth. Even though the odds of winning lotto aren’t great at least they are calculable and finite. At the end of the day, there are only 8 million or so different combinations of numbers and we know that one of them has to win. When it comes to budgeting we are making a prediction about not just the organisation’s priorities, but also its operating conditions and countless other factors outside an executive’s direct control. Unlike lotto where the options are finite, for organisations the number of possible permutations of the future they could face are infinite.

And yet, although the odds of getting our budget right are infinitely lower, most people put more faith in their budget than their lotto numbers. People are generally aware that their chance of winning lotto is low and don’t go and spend their winnings until they’ve won. But in business, people will happily start spending their budget well before they know if their predicted future will come to pass.*

*Those of you who are regular readers of my blog would know that I have a general dislike of budgeting. Although this isn’t the focus of this particular article, I can’t help myself but to reiterate that an overt focus on working to budget encourages people to justify decisions based on the cost rather than their value generation. This leads to some perverse outcomes where people spend their budget on just about anything at the end of the financial year. This is rarely strategic, and has little consideration for value generation. Instead it’s done to ‘protect’ their budget so as to justify similar levels of spending in the next budget period. But perhaps the most perverse part of this is that by spending the organisation’s money on things it may not actually need they are likely to get praise from their manager for their ability to ‘work to budget’.

The problem with budgeting, along with many other planning activities undertaken in organisations are reflected in this quote by U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower

“Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.”

I would argue that in the way in which many organisations approach their planning activities is that they a) put too little thinking into the planning, and b) put too much faith in the plan.

The starting point for any meaningful planning or budgeting activity needs to be ‘we don’t actually know what’s going to happen’. We cannot predict the future accurately and circumstances WILL change. It naturally follows then that any plan that emerges from the planning process has to have the flexibility to change and adapt as new information comes to light.*

*And this is where I’d argue that budgets are particularly insidious. The data and numbers are often presented (and interpreted) as facts rather than as representations and guesses. This is a growing problem with data-driven decision making more broadly. We forget that the data is often just a representation of something else (ie the amount of time someone spends on your website is meant to represent their level of engagement or interest in your products…as opposed to their level of boredom).

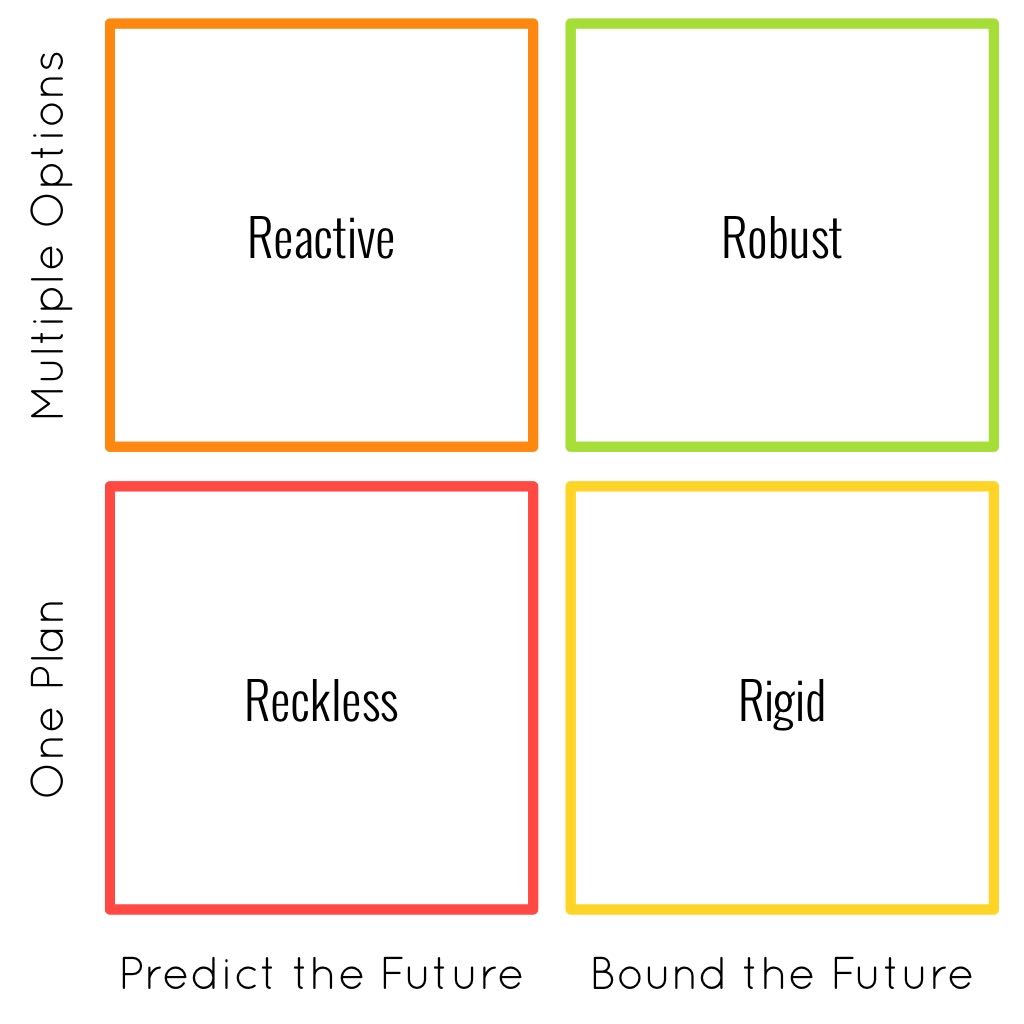

An approach to strategic decision making where only one future is considered (normally the one we prefer the most) and one plan developed is more than just naive, it is Reckless, especially in a world where technology is driving rapid and unpredictable change.

A better proposition, and an approach I see a number of organisations attempt, is to acknowledge that their future is unpredictable and to maintain multiple options that can be enacted if the right conditions emerge. The only issue with this approach is that it’s Reactive and relies on the organisations to be able to identify environmental changes in real time.

An even better approach is to acknowledge the inherent uncertainty that organisations face and take the time to consider multiple futures (or scenarios) during the planning process. Not only will this result in a better plan, it will provide decision makers with the foresight (or memories of things to come) to know if/when the plan is no longer suitable.

But the most Robust approach of all would be to consider multiple futures during the planning process and then have a suite of options you could draw on as conditions evolve and opportunities emerge. This approach not only gives decision makers foresight, it provides them with ready-made plans that can be put into action as required.

These are the foundational ideas of scenario planning, a strategic planning approach pioneered by Royal Dutch Shell back in the 1960s. It was famously used to predict and prepare for the formation of OPEC and assisted South Africa through its post Apartheid transition.

Interestingly enough scenario planning was my last ‘real job’ before moving to Melbourne back in 2010. For close to two years before leaving Perth I worked in Rio Tinto’s scenario planning and strategy team, helping the various business units develop robust plans and strategies for the future. And although a lot of my work since has had a futurist slant to it, it was only in the last couple of months that I’ve had the opportunity to work in the scenario planning space again.

Over the last two months I have been working with a state government agency to develop four 10-year scenarios of their future. These were finally delivered at their leadership team’s strategic offsite last week. Using the same video and sound driven approach I use for my keynotes, each of the scenarios was presented as mini movie with customised soundscape that transported participants into four very unique stories of how the future might unfold. We then provided participants the opportunity to ask questions about the future and work on tables to understand what each of the futures might mean for them.

Now this whole article has made my headline look a lot like clickbait. On one hand I’m suggesting that you can predict the future and on the other I’m telling you the future’s unpredictable. It turns out that the secret to predicting the future is to not fall into the trap of picking just one future. Instead of picking one future, scenario planning seeks to define the boundaries around the future, and then help you prepare for a future that will inevitably fall somewhere in-between.

What this means is I can’t tell you specifically what the lotto numbers will be on Saturday but I can tell you that each of the six winning numbers will be between 1 and 45, and no two of them will be the same.

Let’s check back next week and see if I was right.