Between extreme weather events, political upheaval, regional insecurity, financial instability and global conflicts, there is a general feeling that the world is a little uncertain right now. But is the current level of uncertainty we’re experiencing different from the uncertainties of the past? For instance, are things more or less uncertain now, than after 9/11 or during the Gulf War, or in the lead-up to Y2K*?

* I remember feeling so uncertain about Y2K that I fled England and spent the millennium hiding in the south of Spain…and when I say hiding, I really mean going out to bars and nightclubs.

Measuring Uncertainty

Although there is no simple way to measure uncertainty, we can get a sense of our uncertainty profile by taking a moment to consider four scales of uncertainty: the meta (global), the meso (industry), the macro (organisational) and the micro (personal).

The Meta – Global Uncertainty

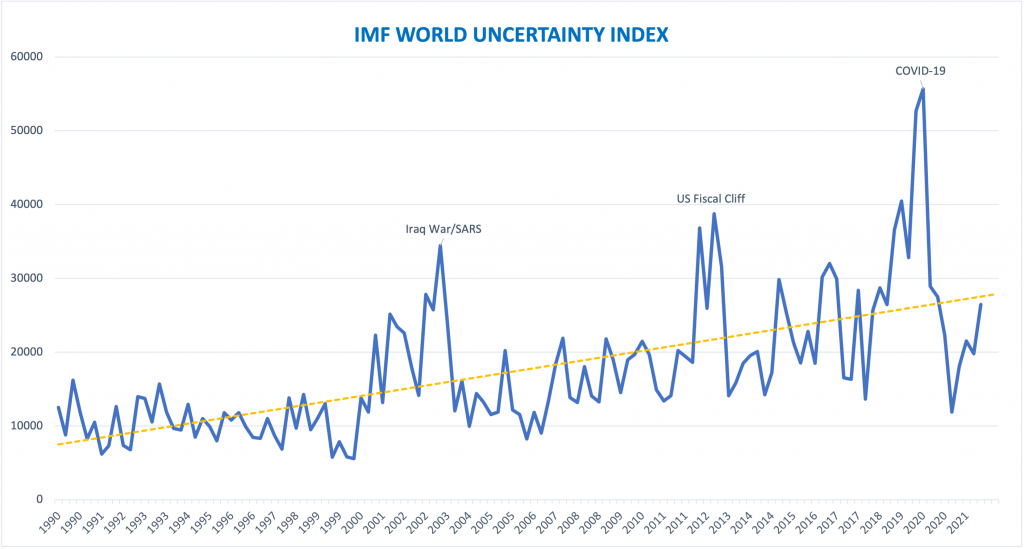

The largest scale of uncertainty is global uncertainty*. At this scale, there have been attempts to quantify the level of uncertainty through metrics. Perhaps the most developed is the International Monetary Fund’s Global Uncertainty Index (GUI). The GUI measures how often the word ‘uncertain’ or (variant of) is used in the Economist Intelligence Unit country reports. Although not entirely scientific, it helps provide a sense of the size and directionality of uncertainty. We can also see the GUI aligns well with known uncertainty events over the last 30 years such as the Gulf War and Covid-19.

*at least until we can get a better grasp of inter-planetary or galactic uncertainty

What the GUI tells us is that in 2019, the global environment was 50% more uncertain than 2013, twice as uncertain as 2005 and three times as uncertain as the 1990s.

So if you’re feeling a sense of uncertainty, this could be why.

The Meso – Industry Uncertainty

Next we can look at uncertainty at an industry scale. Some industries are far more volatile and dynamic than others. For example, technology businesses generally change in a way that is faster and less predictable than utilities (perhaps why our mobile phones go out of date faster than our water heaters).

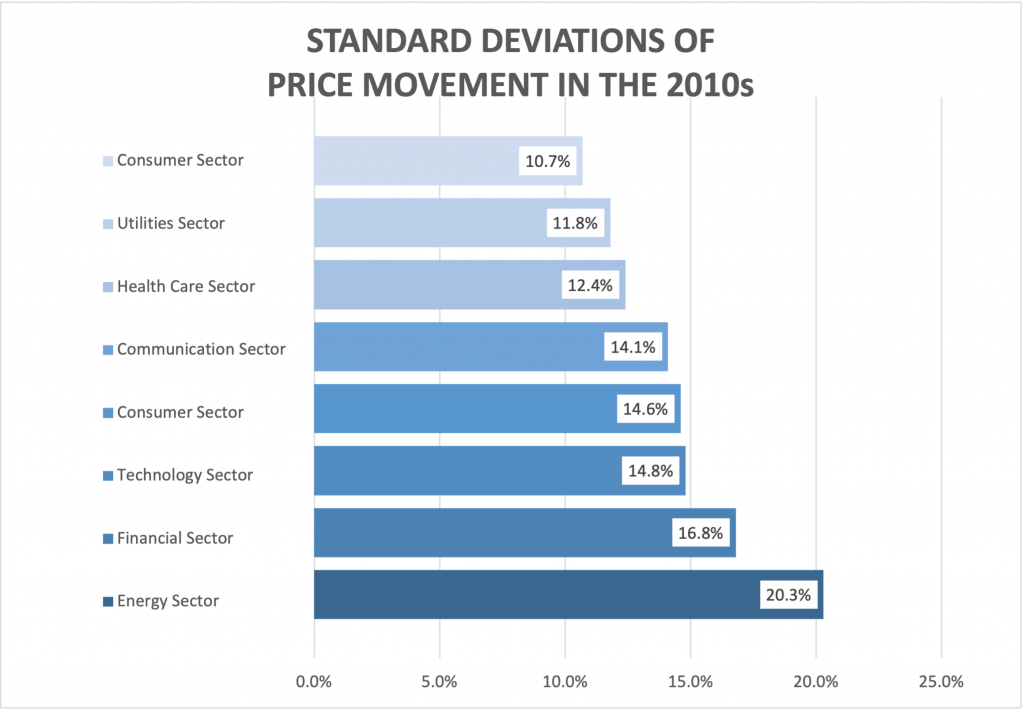

Once again, there are global indexes to help us understand our organisation’s uncertainty profile. For instance, S&P Global recently released a report on the volatility of various industry sectors over the last decade.

The data suggests that the most volatile industry sectors have been Energy, Finance and Technology, and the least volatile have been Consumer Staples, Utilities and Health Care.

Once again, if you operate in a more volatile and uncertain sector, your perception of organisational and even personal uncertainty is likely to be higher.

The Macro – Organisational Uncertainty

Whilst at the meta and meso levels there is quantitative data available; at the macro and micro levels our understanding of uncertainty becomes more qualitative. Step back for a moment and look at what’s happening in your organisation. Has there been a change in leadership, increased mergers and acquisition activity, a shift in industry focus or new product launches (anything that has a direct impact on your organisation, but not necessarily on the organisations around you)?

Although more difficult to quantify, macro uncertainty has a far more direct impact on us. It is the uncertainty that we deal with each and every work day and may even amplify the ‘general feeling of uncertainty’ at the Meta and the Meso level.

The Micro – Personal Uncertainty

Finally we have uncertainty at a personal level. This could be uncertainty linked to our sense of job security, personal finances or our relationship with loved ones. These are the uncertainties that are hardest to escape from. Unlike macro uncertainties, they don’t just exist within the 9 to 5, they are with us all the time.

Uncertainty is certain

The Greek philosopher Heraclitus was quoted as saying, “Change is the only constant in life.” And just as change is constant it is also true that ‘Uncertainty is certain’.

It’s not whether things are certain or uncertain, it’s the degree of uncertainty that we’re dealing with and our capacity to manage it that ultimately matters.*. Perhaps a better question to ask than ‘are things more uncertain?’ is ‘what might we need to do differently if we know that they are?’.