It’s time for you to either get on the bus or get off. Are you going out or staying home? Is reading this a good use or bad use of your time?

Maybe it’s too early to make that call…or maybe it isn’t.

How often do you find yourself being given binary choices and your gut reaction is ‘maybe’? On the surface, answering ‘maybe’ to a binary (yes/no) question appears illegitimate and is often a source of great frustration for the person asking the question (who ‘just wants to know where you stand’). But if your gut reaction to a binary question is ‘maybe,’ it’s likely the question is more illegitimate than your answer.

The framing of a question as black and white when there could be a multitude of shades, tints, and tones is known as Binary Bias. Having a binary bias is a way of making a complex and uncertain world easier to comprehend. It allows us to put things, or people, into categories which lowers our cognitive load, but sometimes these categories are not a fair reflection of where someone really stands.

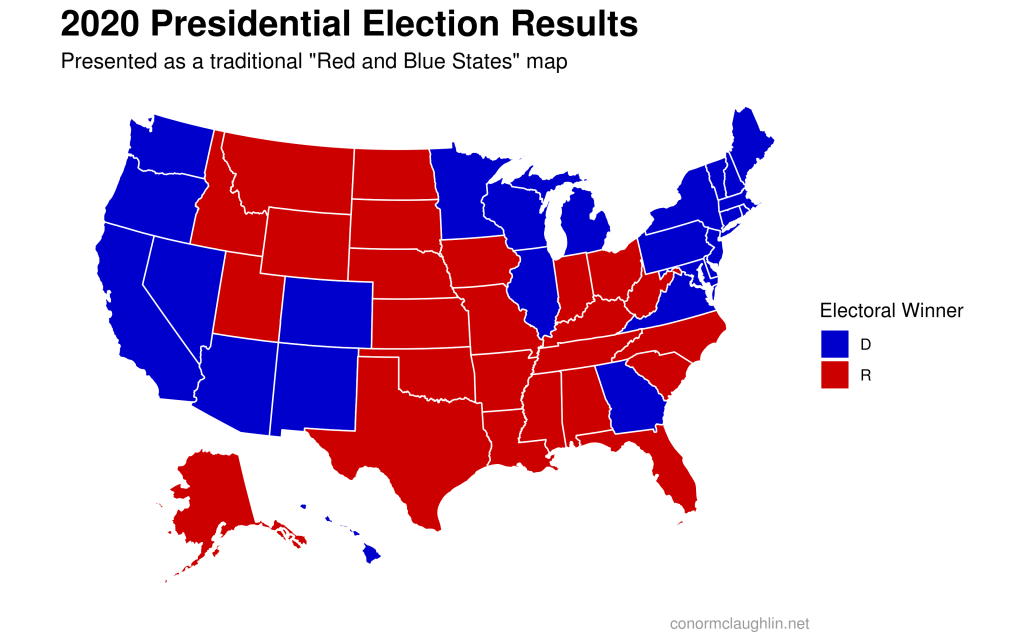

A lovely pictorial expression of this can be found in election results (stick with me here). This map created by Conor McLaughlin shows the results of the 2020 US Presidential Election. The red-coloured states voted for the Republican candidate Donald Trump, and the blue-coloured states voted for the Democrat candidate Joe Biden.

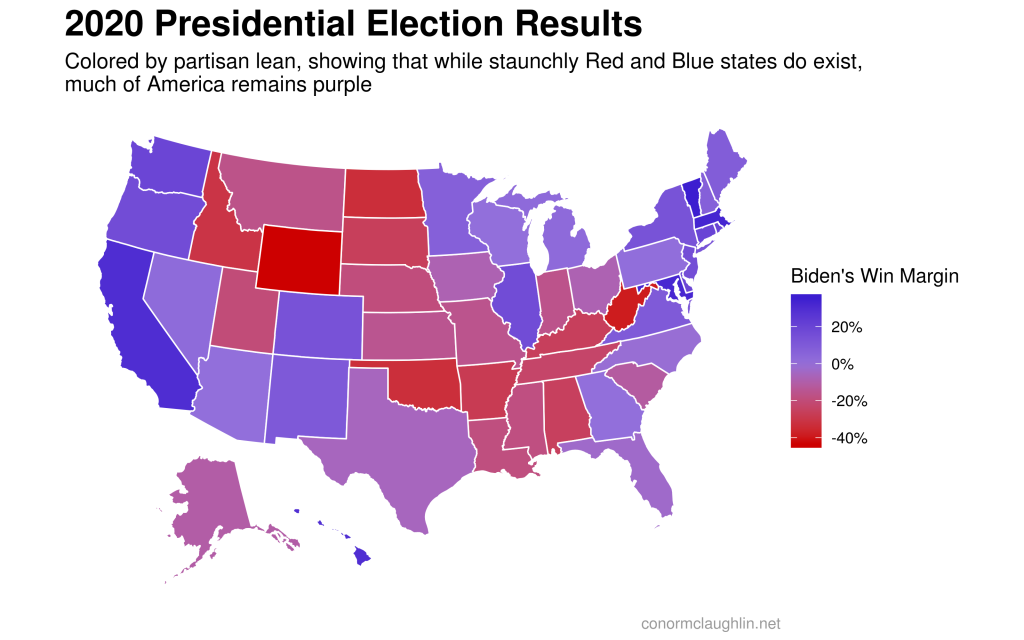

But the problem with this map is that it’s overly simplistic. It represents a binary position of red or blue when in fact every state contains a combination of both. And when we combine different quantities of red and blue, we get different shades of purple. A more representative map of election results would look like this.

Even this map overstates how red or blue individual states are. In the 2020 election, the most red state was Wyoming, in which more than 30% of voters voted blue (Democrat). And the most blue state had nearly 8% of voters voting red (Republican). For some states, such as Georgia, the difference between red and blue was less than half a percent.

Why does this matter? Because it’s difficult to understand the nuance of people’s position and find common ground when we define them as either 100% in or 100% out.

Another interesting example of this is in conversations about climate change. In the climate change debate (as it’s rarely conducted as a conversation or enquiry), we are expected to take one of two extreme positions. Either we can be a Climate Change Denier or a Climate Change Evangelist. Yet research by Yale’s Program on Climate Change Communication suggests that about 29% of 18+ year-olds Americans are extremely sure global warming is happening and another 3% are extremely sure it isn’t. If these represent the black and white positions of the climate debate, the vast majority of people (about 68%) are ‘maybes’.

In truth, the climate conversation is both too complex and too important to frame as black and white. For the conversation to move forward, we need questions that allow us to explore where people really stand. Other questions we could pose include:

- On a scale of one to ten, how confident are you that climate change is happening?

- If you are relatively confident climate change is happening, how confident are you that industrialisation and other human interventions are the main cause?

- How likely do you think it is natural cycles are also at play?

- If you believe the climate is changing, what are some of the positive and negative outcomes we might need to deal with?

- If we face significant negative climate change risks, what (if anything) should we do to ensure against it?

- If climate change is happening, how comfortable do you feel we will be able to innovate our way out of it?

On the surface, asking these questions appears harder, far more time-consuming, and significantly messier than the binary choice of climate change denier or climate change evangelist. But what decades of frustration in the climate change debate has shown us is that only allowing binary responses to complex and uncertain questions means a lot of people end up sitting on the fence. We get definitive maybes. So, in the pursuit of simplicity and efficiency, we end up going nowhere.

Think about where you might be asking for a binary decision to a complex problem. Although your final decisions may end up as binary (do you fund the new library, engage that consultant, or replace the old CRM system), the investigation needs to allow for messiness and nuance. And if the decision is being made by a diverse group of decision-makers such as a board of directors or councilors, the process should also allow for common ground to emerge and key differences to be identified.

At the end of the day, the quality of decision-making isn’t defined by the speed of the decision but the effectiveness of the process.

Simon